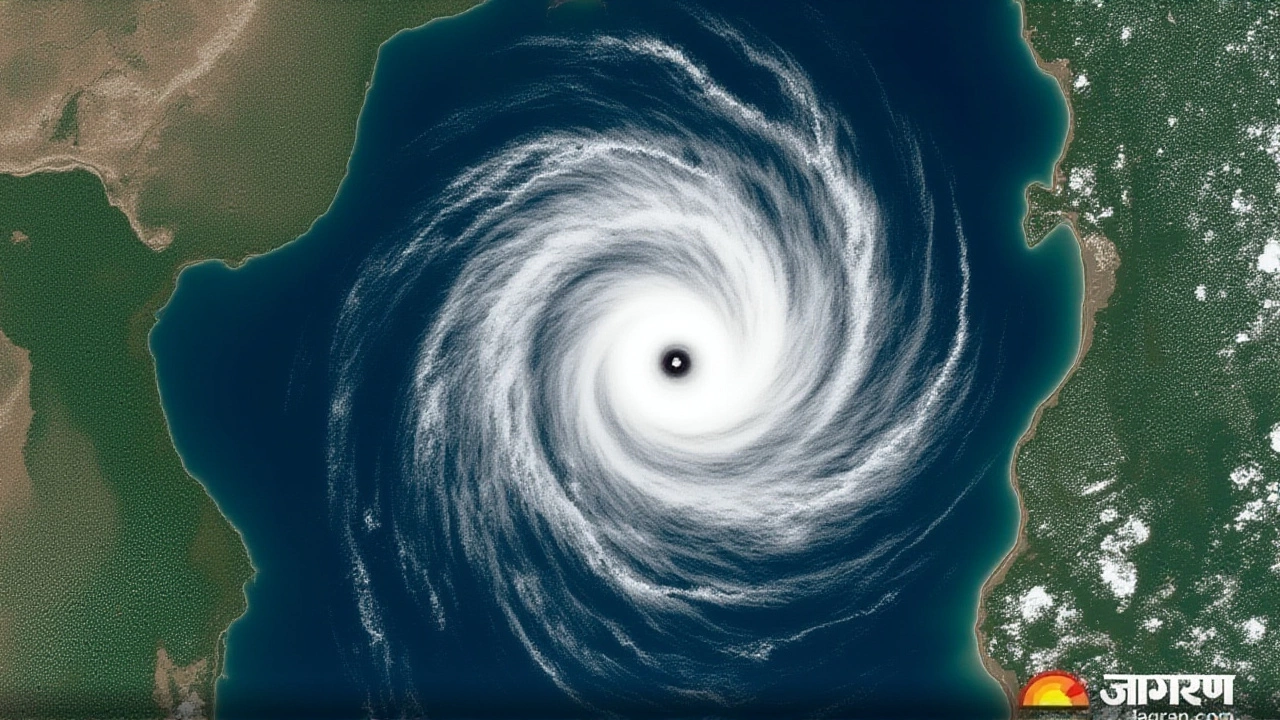

When India Meteorological Department sounded the alarm on October 27, 2025, it wasn’t just another storm warning — it was a full-blown emergency for millions. Cyclone Montha, having rapidly intensified into a severe cyclonic storm by 5:30 a.m. IST on October 28, was poised to slam into the Andhra Pradesh coast between Machilipatnam and Kalingapatnam with winds gusting up to 110 km/h. The storm’s center, located just 190 km south-southeast of Machilipatnam, had already churned up the Bay of Bengal with terrifying speed, triggering a cascade of extreme weather across nearly half the country. What makes this different? It’s not just the wind. It’s the rain — relentless, record-shattering, and relentless again.

Unprecedented Rainfall Across India

The IMD’s forecast reads like a disaster checklist. From Kerala to Assam, from Bihar to Maharashtra, no region was left untouched. Isolated pockets in Coastal Andhra Pradesh and Telangana were warned of extremely heavy rainfall — 21 cm or more in just 24 hours. That’s nearly eight inches. In places like Rayalaseema and Yanam, roads turned to rivers before dawn. Meanwhile, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, and Coastal Karnataka braced for 12–20 cm of rain, while Bihar and Jharkhand faced a dual threat: direct rainfall and downstream flooding from rivers swollen by upstream deluges. The rainfall wasn’t just widespread — it was staggered. Each day brought a new wave. October 28 saw the worst of it in Telangana and Andhra. By October 30, the focus shifted to Bihar and West Bengal, where the Ganga and its tributaries were already rising. Even distant regions like East Rajasthan and Sikkim weren’t spared. The pattern? A slow-motion flood, moving northward like a tidal wave with no end in sight.Urban Chaos and Rural Ruin

In Hyderabad, waterlogged streets paralyzed morning commutes. Metro services halted. In Visakhapatnam, underpasses became death traps. Emergency services reported over 300 rescues by noon on October 28. Meanwhile, in rural Bihar, farmers watched helplessly as standing paddy crops — already stressed by a delayed monsoon — were submerged under muddy water. The IMD warned of localized landslides in the Western Ghats and the Himalayan foothills, with villages in Assam and Meghalaya cut off from supply routes. The impact wasn’t just physical. Power outages spread across five states. Mobile networks failed in 17 districts. Schools in Andhra Pradesh and Odisha shut down through October 30. The Central Water Commission urged residents to monitor river levels in real time, as the Godavari and Mahanadi basins were expected to breach danger levels by October 31.

Government and Global Response

The Indian government activated the National Disaster Response Force (NDRF) in 18 states. Helicopters were deployed for aerial surveys. In Kolkata, the U.S. Consulate General issued a rare weather alert for its staff, advising evacuation from low-lying areas — a sign of how seriously foreign missions were taking the threat. Local authorities in Andhra Pradesh ordered mandatory evacuations in 14 coastal districts, with over 180,000 people moved to relief centers. The India Meteorological Department — a century-old institution since 1875 — issued its warnings with unusual urgency. Each forecast, valid from 8:30 a.m. to 8:30 a.m. the next day, was updated every six hours. “This isn’t just weather,” said a senior IMD official, speaking anonymously. “It’s a systemic stress test. We haven’t seen this combination of wind, rain, and timing since 2018’s Fani.”Why This Storm Is Different

Cyclone Montha didn’t form in isolation. Sea surface temperatures in the Bay of Bengal were 1.8°C above average. The Indian Ocean Dipole, a climate pattern that influences monsoon intensity, was in a strong positive phase — a setup that favors more intense cyclones. Scientists at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology had flagged this risk as early as September. What made Montha dangerous wasn’t just its strength — it was its path. Unlike most cyclones that veer north into Bangladesh, Montha was tracking straight toward the densely populated Andhra coast, where infrastructure remains fragile after years of underinvestment. Even the temperature drop added to the chaos. Northwest India saw minimum temperatures plunge by 2–5°C over three days. In Delhi, people bundled up — but the cold was irrelevant compared to the flooding. The real crisis was in the south and east, where wet soil turned to sludge, and drainage systems — designed for 20-year rainfall events — collapsed under 100-year deluges.

What Comes Next

The immediate threat eases after November 1, but the aftermath lingers. The Central Water Commission expects floodwaters to take 7–10 days to recede in Bihar and West Bengal. Crop damage is estimated at over ₹1,800 crore ($2.3 million), with sugarcane and banana plantations in Telangana hit hardest. Insurance claims are already flooding in — but only 18% of affected farmers have coverage. The real question? Will this be a wake-up call? In 2022, Odisha spent ₹4,000 crore on cyclone-proof housing after Fani. Andhra Pradesh, meanwhile, still has over 60% of its coastal villages in kutcha homes. If Montha teaches us anything, it’s that preparation isn’t optional. It’s survival.Frequently Asked Questions

How is Cyclone Montha different from previous cyclones like Fani or Amphan?

Unlike Fani (2019) or Amphan (2020), which primarily affected Odisha and West Bengal, Cyclone Montha’s track targets Andhra Pradesh and Telangana — regions with less cyclone-hardened infrastructure. Montha also formed during a rare positive Indian Ocean Dipole phase, which boosted sea temperatures and rainfall intensity beyond typical seasonal norms. Its slow movement over the Bay of Bengal allowed it to gather more energy than most October cyclones.

Which areas are at highest risk for riverine flooding?

Bihar, Jharkhand, and West Bengal face the highest riverine flood risk due to upstream rainfall feeding the Ganga, Kosi, and Damodar rivers. The Central Water Commission has flagged the Ghatsila and Bhagalpur districts as critical zones, with water levels expected to exceed danger marks by November 2. Residents near the Gandak and Son rivers are advised to evacuate if warned.

What should people do if they’re trapped in waterlogged areas?

Stay indoors if safe. Avoid walking or driving through floodwaters — just 15 cm of moving water can sweep away a car. Call 1070 (state disaster helpline) or 112 for rescue. Keep mobile phones charged and use battery packs. Do not touch fallen power lines. In urban areas, move to upper floors and signal from windows if help is delayed. Avoid using gas stoves in flooded homes due to risk of gas leaks.

How long will the rainfall last, and when will things return to normal?

The heaviest rain ends by November 1, but residual flooding will persist for 7–10 days in Bihar and West Bengal. Power and telecom restoration may take 3–5 days in rural areas. Schools and offices are expected to reopen by November 5 in most states, though Andhra Pradesh and Odisha may delay until November 8 due to infrastructure damage. Crop recovery will take months, with some farmers losing entire harvests.

Why did the U.S. Consulate issue a weather alert?

The U.S. Consulate General in Kolkata issued the alert because its staff and facilities in eastern India are vulnerable to flooding, power outages, and transport disruptions. This is rare — consulates typically issue alerts only for extreme, life-threatening conditions. The move signals that even international agencies view Montha as a major regional emergency, not just a local storm.

Is climate change making cyclones like Montha more common?

Yes. Data from the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology shows a 40% increase in severe cyclones over the Bay of Bengal since 2000. Warmer ocean temperatures, reduced wind shear, and altered atmospheric patterns are creating ideal conditions for rapid intensification. Cyclone Montha is the fourth severe cyclone to hit India in 2025 — a record pace. Scientists warn this trend will continue unless global emissions are drastically cut.